Far from the formalities which characterize the international system is a coterie of political entities that quietly defy the very essence of statehood. Dubbed de facto, or unrecognized, states, such territories are self-governing, hold elections, possess institutions and are engaged in the world — but must do so under the cloak of diplomatic invisibility.

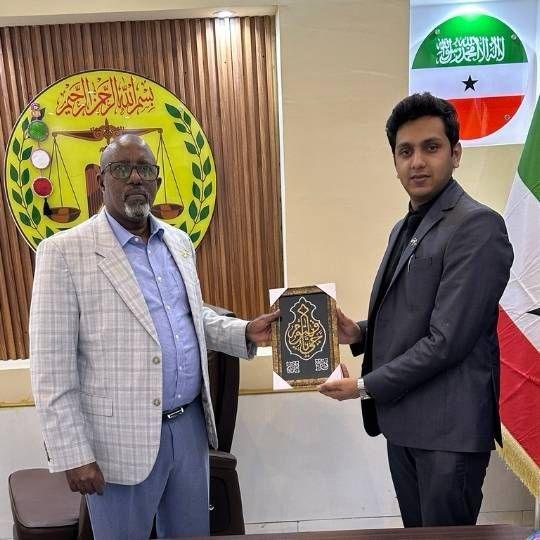

Somaliland, a de facto state in the Horn of Africa, is one of the most prominent long-term examples. Somaliland has managed to build a functioning democracy, secure the peace and generate its own currency system and its judicial system, all of which are the same penned down in the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States (1933). Still, more than three decades on, no member state of the United Nations formally accepts it.

Somaliland: The Country in Everything But Name

Somaliland’s modern history dates to 1991, when Somalia’s central government crumbled. Somaliland was a British protectorate from 1884 to 1960, when it gained independence and united as scheduled with the former Italian Somaliland, the trust territory of the United Nations (UN) to which Italy agreed “to promote”, to form the Somali Republic. But being marginalized for decades and fighting a civil war eventually resulted in a unilateral declaration of independence.

Somaliland today operates as a nation-state in all but name. It has conducted several presidential and parliamentary elections, which have been commended by the international community, including observers from bodies like the International Republican Institute, and constructed strong institutions including a national police force, judiciary and a bicameral legislature. In practice Freedom House has consistently rated Somalland higher than many recognised African states with respect to civil liberties and press freedoms (Freedom House, 2023).

Regardless of these accomplishments, Somaliland is yet to be recognized and the road toward recognition is blocked especially by the African Union which sticks with colonial boundaries not to set precedent for the appeasement of other separatist claims (Herbst, 2000). In the words of scholar Scott Pegg (1998) Somaliland finds itself in a “twilight zone of sovereignty” — it is internally wholly functional but externally it is inoperable.

-Residing in the Gray Zone: International Comparisons

Somaliland belongs to a wider category of the global de facto or partially recognized states. All have their distinct histories, most marked by conflict, colonial legacies and major-power politics. Some of them include:

Taiwan: A democratic and sovereign nation with a >$700 billion economy, but absent from the UN because of the One China Policy and Beijing’s coercion.

Transnistria: A breakaway region from Moldova that has its own currency and military but is heavily dependent on Russian assistance.

Abkhazia and South Ossetia: Recognized by Russia and a handful of others, but reliant on Moscow.

Northern Cyprus: Recognized only by Turkey, but operates with full state institutions.

Nagorno-Karabakh (Artsakh): Became a puppet after the 2023 Azerbaijani invasion.

Palestine: Recognized by more than 130 countries but not a full UN member because of U.S. and Israeli opposition.

Kosovo: Recognized by many in the West, but blocked at the UN by Russia and China.

These examples show that ability is not a sufficient basis for credit. Some still weathered economic growth (Taiwan); others existential threats (Artsakh).

-Governance Unrecognised: The Best Performers?

If statehood was purely about function then many of these de facto states would already be considered valid. Four requirements are defined under the Montevideo Convention:

- Defined territory

- Permanent population

- Functioning government

- Foreign relations capability

Somaliland fits the bill — and some. Its democratic elections, rule of law and relative peace are much further advanced than those in its parent country Somalia.

Historians such as Charles King (2001) and Nina Caspersen (2015) argue that not all unrecognised states are weak, in terms of governance and control over territory and resources, and often have strong internal legitimacy, albeit that ultimately neither is guaranteed to result in successful statehood. The concept of earned sovereignty (Williams et al., 2003) reinforces this – acts of responsible governance and democratic performance allow states to accrue legitimacy.

Others are less self-governing client states, more like Transnistria or Abkhazia, what we too-brittle analysts call puppet regimes: dependent on foreign patrons and without the institutions or capacity for clear and transparent governance.

Recognition as Power: The Politics of State Recognition

So why do some territories get the recognition that others languish without? The solution is not legal — it’s political.

As Hersch Lauterpacht (1947) has observed, recognition is a political act that is influenced by the interests of powerful states. US and EU backing won Kosovo recognition. Taiwan is isolated because of China’s global weight. US-Israeli alliance*s block recognition for Palestine.

Somaliland itself does not have a geopolitical patron. None of the great powers have specified this question as something that is in its viewpoint strategically necessary. This is why Somaliland could ultimately become what Robert Jackson (1990) refers to as a ‘quasi-state’: functioning as a state internally, but not having anyone else pay attention to it at all. Yet ironically, it hasn’t been enough to just be peaceful, democratic and stable.

Rethinking Statehood in a Divided World

Somaliland questions the Westphalian model of the state. In an age of transnational actors and fluid sovereignty, we must develop new ways of thinking about, and new ways to engage with, unrecognized states.

Scholars such as Stephen Krasner (1999) and David Lake (2003) suggest alternative frameworks, such as:

- Graduated recognition

- Earned legitimacy

- Functional engagement

They all reward performance, not politics, and could accommodate Somaliland with some level of inclusion — observer status at The U.N. agencies, trade relations, regional partnerships — without jumping the gun on official recognition. This would recognise Somaliland’s successes while minimising the risk of diplomatic isolation.

Conclusion: Hope and Invisibility

Somaliland is a living success (and cautionary) story. It is an example of how people can do peace, democracy and effective governance even without external assistance. But it also suggests the constraints of sovereignty without recognition.

At a time the world is dealing with increasingly autonomous movements, fractured authorities, it is the concept of recognition that we should be seizing: A performance-based recognition that rewards good governance and democratic achievement.

Only then can places like Somaliland be recognized, not as oddities, but as trailblazers for a more inclusive system of global relations.