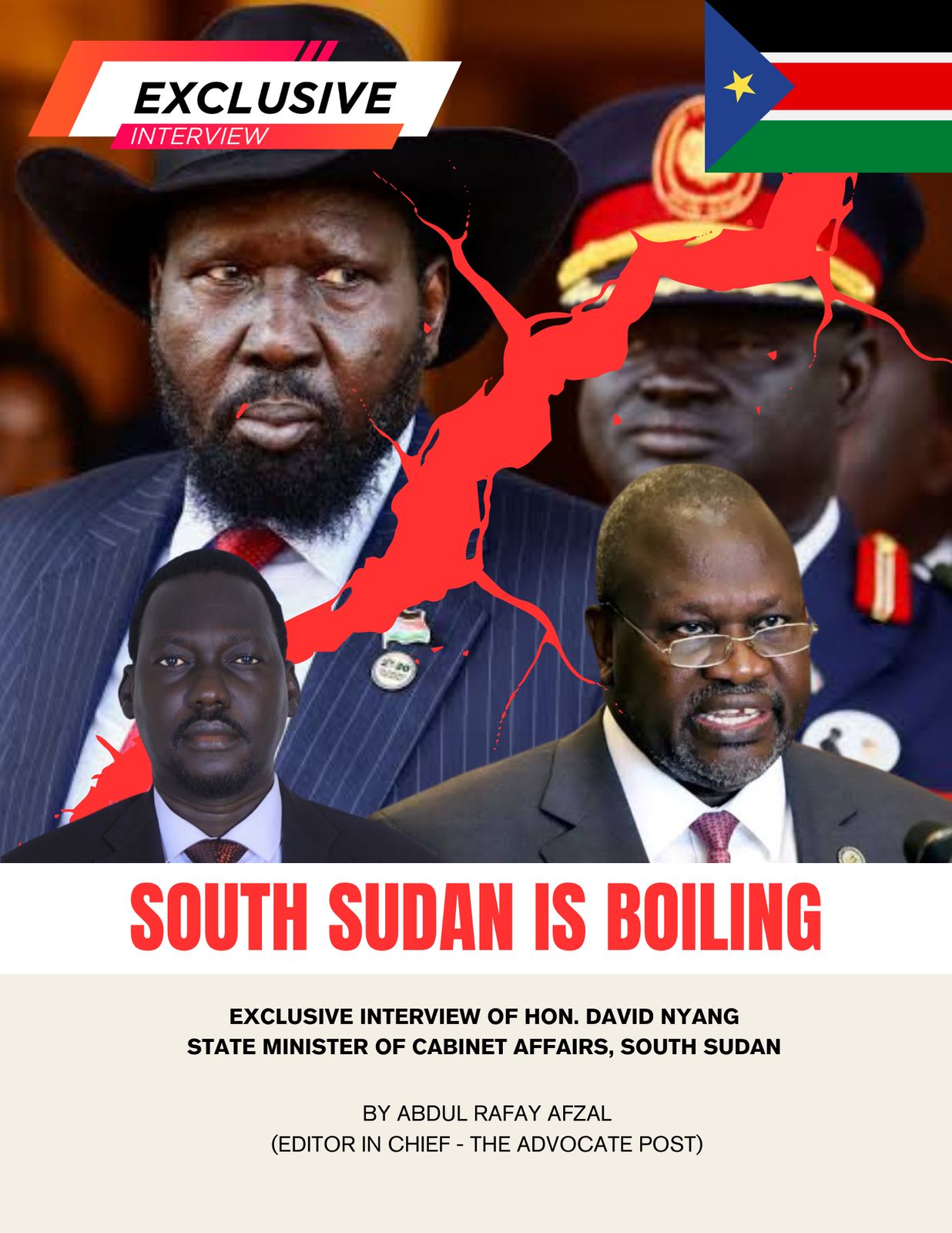

By Abdul Rafay Afzal (Editor in Chief)

South Sudan, the world’s youngest nation, is teetering on the brink of renewed civil war. The recent house arrest of Vice President Dr. Riek Machar has intensified fears of a total breakdown of the 2018 peace agreement, which ended a brutal five-year conflict. In an exclusive interview with The Advocate Post, David Young, South Sudan’s Minister of Cabinet Affairs and acting governor of oil-rich Upper Nile State, pulls no punches:

“The peace deal is already collapsed for many of us.”

From tribal militias to chemical weapons, oil dependence to Somaliland’s strategic port, Young reveals the explosive realities of South Sudan’s crises—and why the international community must act now.

Political Crisis: “The Army Is Divided Along Tribal Lines”

Q: The vice president’s arrest has sparked fears of a return to war. Is the 2018 peace agreement dead?

The glue holding South Sudan together was this agreement. Now, the training camps for unified forces are dismantled, and the army is split—Dinka loyalists back President Salva Kiir, Nuer fighters back Machar. Without a national army, we’re one spark away from war and it could break the country in two.

Q: Opposition leaders declare the 2018 peace agreement “ended.” Is this accurate?

The agreement had two critical pillars: unified security forces and power-sharing. Neither exists today. The training camps for joint forces have been dismantled by fighting between Kiir and Machar loyalists. When your army splits along tribal lines – Dinka commanders versus Nuer units – that’s not a peace deal, that’s a powder keg. There is no National but Tribalistic Character.

Q. Is the division only in the military, or does it extend to key ministries like Foreign Affairs?

No, The Foreign Ministry and others still speaks with one voice…because no faction wants to lose international recognition. But open any other ministry and you’ll find Dinka and Nuer officials keeping separate books. It’s institutionalized distrust.

Q. How you see the Role of Mediators Right now?

For God Sake we want someone to mediate in between the Government and Opposition. IGAD’s envoys are trying and calling Kiir and Machar in the same. Apart from that The U.S., The UK and Netherlands also Kenya and Ethiopia along with AU and EU are reduced to issuing statements while Uganda actively fuels the conflict by backing Kiir’s faction.

Q. Youth unemployment in South Sudan exceeds 80%. What urgent measures are being taken to address this?

The government recognizes youth unemployment as a critical issue threatening social cohesion and economic progress. Currently, we are focusing on vocational training programs and partnerships with local businesses to create job opportunities.

However, instability has hindered large-scale initiatives. Many projects rely on international NGOs and UN agencies like WFP and UNICEF for implementation. Moving forward, we aim to strengthen public-private partnerships to boost employment, but lasting progress depends on achieving nationwide peace. The suspension of USAID support has created immediate strains. Many NGOs and UN agencies depended on this funding for lifesaving programs.

Q. How is South Sudan tackling its oil-dependent economy amid global shifts and pipeline disruptions?

The economic challenges are severe, but we are pursuing a multi-pronged approach. Immediately, we’re tightening monetary policy to curb inflation and stabilize the currency, while prioritizing non-oil revenue collection at borders. However, long-term solutions require diversification. Agriculture is a priority—South Sudan has fertile land capable of becoming the region’s breadbasket. We’re also exploring mineral extraction (gold, iron ore) and renewable energy projects like solar to align with global energy shifts.

Pakistan was one of the countries that actually recognised the independence of South Sudan and we have very good relationship. In 2012 Prime Minister of Pakistan Yousuf Raza Gillani also visited Juba and signed different agreements for cooperation.

Q: With South Sudan’s oil exports blocked through Sudan and alternative routes stalled, how viable is Somaliland’s Berbera port as a solution given your historical ties?

Facing an economic crisis due to the year-long shutdown of oil exports through Sudan, South Sudan is urgently exploring alternative routes, with government officials acknowledging that while Somaliland lacks international recognition, its strategic Berbera port could offer a potential solution given historical ties (Somaliland’s representative office in Juba and its delegation attending South Sudan’s 2011 independence). The government is currently prioritizing more immediate options like the Ethiopia-Djibouti corridor and Kenya’s delayed Lamu Port project, but maintains that if Ethiopia’s deal with Somaliland progresses, South Sudan would consider utilizing Berbera as an option, balancing diplomatic sensitivities with the desperate need to restore oil revenue streams amid hyperinflation and currency collapse. The distance is challenging, but for a landlocked nation, every option must be studied. Right now, Djibouti remains more feasible, but we don’t rule out future Somaliland cooperation.

Q. How is South Sudan expanding cooperation with Muslim-majority nations?

While we maintain strong ties across the Muslim world – from Egypt and Libya to the Gulf Cooperation Council states – our partnership with Pakistan holds unique strategic value, particularly in defense cooperation. Pakistan has not only contributed troops to UNMISS but has trained generations of our senior military officers, providing critical counterinsurgency and institutional expertise that directly strengthens our security forces. This military assistance complements our broader relationships with Muslim nations: the UAE and Saudi Arabia support development projects, while Qatar mediates peace processes. However, Pakistan’s combination of UN peacekeeping, military training, and humanitarian aid during our conflicts makes it an indispensable partner. As we stabilize, we’re working to elevate all these relationships and expanded Pakistani military training programs. The common thread is mutual respect; whether Christian-majority or Muslim-majority, we share the goal of a secure, prosperous South Sudan.

Q: How does South Sudan balance competing interests of global powers like China, the US, and UAE while protecting its sovereignty?

South Sudan maintains a pragmatic, interest-based foreign policy. While the US midwifed our independence and remains a key partner, China’s dominant role in our oil sector – with existing infrastructure investments – creates unavoidable interdependence. The UAE brings critical infrastructure financing, particularly in ports and logistics. Our approach is neither ideological nor exclusive; we partner where mutual benefits exist. The complexity shows in our relations – even as the EU funds development projects, it simultaneously imposes sanctions, mirroring the US dynamic with partners like Pakistan. Ultimately, we prioritize sovereignty: Uganda’s involvement in our conflicts demonstrates how regional actors also pursue their interests. The Foreign Ministry carefully navigates these relationships, recognizing that in a multipolar world, non-aligned flexibility serves us best.

Q: How is South Sudan addressing intercommunal violence in Jonglei while implementing anti-corruption reforms?

The Jonglei violence exemplifies our core challenge – local conflicts becoming national crises. While we deployed peacekeepers, punitive measures backfired. The solution requires localized reconciliation through tribal elders and economic programs to disrupt cycles of cattle raiding. On corruption, we acknowledge our ranking among the world’s worst – weak institutions enable graft. Recent measures include: 1) Public sector payroll audits exposing ‘ghost workers’, 2) Oil revenue tracking with Norway’s NORAD, and 3) The Vice President’s anti-graft unit targeting low/mid-level officials first to build credibility. Is it politicized? In fragile states, every action has political dimensions, but the economic emergency makes this a survival imperative. Both issues – violence and corruption – demand institutional rebuilding, not quick fixes.

Q: What are South Sudan’s top three priorities for the next 12-20 months, and how do you personally believe the country can achieve stability?

Our immediate priorities are clear: First, de-escalating conflict through inclusive dialogue – we must prevent renewed war by bringing all factions, including holdout groups, into the revitalized peace agreement framework. Second, delivering basic services – quality education, healthcare, and youth employment programs to address root causes of instability. Third, rebuilding regional partnerships for economic recovery, particularly in agriculture and infrastructure.

Personally, I emphasize that political will is decisive. The 2018 peace agreement remains our blueprint, but implementation gaps fuel tensions. We need to: 1) Fast-track security sector reforms to integrate opposition forces, 2) Decentralize governance to address marginalization grievances, and 3) Partner with neighbors like Kenya and Ethiopia on cross-border trade routes while engaging the diaspora for skills transfer. The alternative – cyclical violence – is unacceptable to our people who’ve endured enough.

This Post Has 10 Comments

This interview really highlights the urgent need for international intervention. With the peace agreement unraveling and the army divided, the global community must step up to prevent a return to civil war.

This interviewBlog Comment Creation really highlights how fragile the peace process in South Sudan still is. The fact that the army is divided along tribal lines and the unified forces are falling apart shows how urgently the international community needs to re-engage—not just with aid, but with real diplomatic pressure. Without that, the cycle of instability is bound to repeat.

The collapse of the peace deal is tragic but, sadly, not surprising given the deep-rooted tribal loyalties. I’m curious—are there any grassroots movements or civil society groups still pushing for unity on the ground?

This interviewBlog Comment Analysis offers a sobering view into the deep fractures within South Sudan’s military and political landscape. David Nyang’s point about the army dividing along tribal lines is particularly alarming—it signals not just a failed peace deal, but a deeper structural breakdown that can’t be solved with political rhetoric alone. It’s a clear call for more nuanced international engagement before things spiral further.

David Nyang’s candid assessment of the disintegration of the peace deal is deeply troubling. It’s alarming that training camps for unified forces have been dismantled—how can there be a future without a functioning, unified national army?

This interview really highlights how fragile the 2018 peace agreement has become—especially with the army fracturing along tribal lines. David Nyang’s candid remarks are a stark reminder that without real unity and international pressure, South Sudan risks slipping back into full-scale conflict.

Ah, the classic ‘peace deal is collapsing’ drama. At this point, they should just sell tickets to the next civil war—I’d get in line for that show, ya know?

So, the army is divided like my friends at dinner when it’s time to split the bill—good luck finding common ground, right?

This interview really underscores how fragile South Sudan’s stability remains, especially with the army split along tribal lines. It seems like the collapse of the peace deal isn’t just a political failure but also a warning about what happens when security forces are never fully unified. I wonder if regional actors like the AU or IGAD can realistically step in before the situation unravels completely.

This interview really highlights how fragile the peace process in South Sudan still is, especially with the army’s deep tribal divisions and the collapse of unified training efforts. It’s a stark reminder that political agreements mean little without real structural reform and trust-building at the community level. I’d be interested to hear more about what regional actors, like the AU or IGAD, are doing to prevent another full-scale conflict.